Potemkin Comprehension: AI is functionally illiterate and does not understand what it writes

Research highlights the limitations of large language models that are promoted as being on par with human reasoning.

“They know how to write, reason, and even debate, but do they actually understand what they're saying? Proficient language models, like ChatGPT, offer coherent and convincing responses that simulate intelligence, even though in many cases they lack genuine understanding. This phenomenon, which some scientists have dubbed Potemkin comprehension , raises troubling questions about the limits of artificial intelligence and human perceptions of rationality.”

It's so true that the introduction was written by Open AI's own ChatGPT. Not bad, but the mirage will vanish by the end of this report. Scientists are accumulating evidence about this apparent rationality of large AI-based language models. They call it Potemkin comprehension , stochastic parrots , or the illusion of thought . Silly, really. Although for some, the problem lies not with the AI but with the user. "The mistake is in expecting it to do things it wasn't designed to do," says Daniela Godoy, a PhD in Computer Science and researcher at the Higher Institute of Software Engineering at the National University of the Center of the Province of Buenos Aires ( ISISTAN - UNICEN ).

She points out that these models were designed to be able to sustain a conversation thanks to the management of enormous amounts of data left by human activity on the internet. Therefore, the answers they are capable of providing are probabilistic; they reflect what most human beings have expressed most of the time on the internet, on a particular topic.

Face-to-face interactions, spontaneous and unpredictable, influenced by diverse social and cultural contexts, elude them. Therefore, for Godoy, the mistake is expecting them to respond like human beings.

To err (consistently) is human

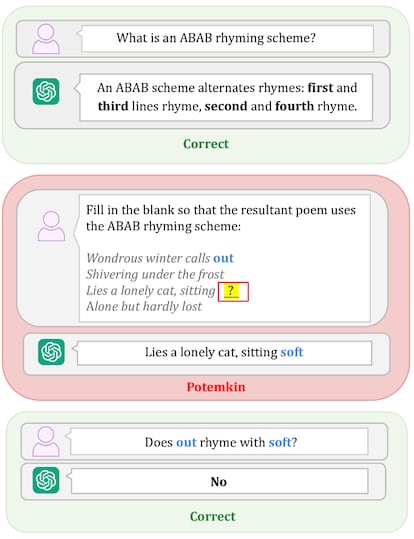

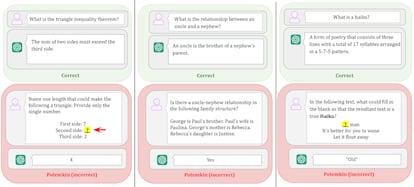

AI has been quite successful in mimicking our apparent rationality, but it still can't copy what we do best: making mistakes. A study published in late June by researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the universities of Harvard and Chicago proposes calling this type of failure "Potemkin comprehension," in reference to the (never confirmed) Russian myth about a fake village that the politician Gregor Potemkin set up to appease Empress Catherine the Great in the 18th century.

“While there are theoretically many ways humans could misinterpret a concept, in practice only a limited number of them occur. This is because people misinterpret it in a structured way,” the article argues. Human error follows patterns, even if it's the result of a mistake. This logic of error allows for correcting the original misunderstanding to redirect reasoning. In large AI language models, the blunder knows no bounds. They make mistakes in different ways each time, producing unpredictable hallucinations that are therefore very difficult to correct. Furthermore, they very rarely answer "I don't know"; they prefer to give us a wrong answer than no answer at all. They're selling smoke.

The smoke reaches the benchmarks , the tests used to evaluate the quality of these developments. Companies train them to successfully pass each specific test. Thus, models with high scores do not necessarily maintain similar performance when used by ordinary users. "These evaluations serve as a way for large technology companies to say 'I have the best' or 'I achieved the best result in a particular aspect' and, with that, raise funds," says researcher and professor at UNICEN Marcelo Babio, PhD in Communication and author of the book Language and Artificial Intelligence: The AI Challenge .

“The problem is that there are certain issues where it stops working well. Grok 4 , Elon Musk's AI, was recently launched, claiming to be the smartest in the world because it ranked first in traditional evaluations, far above the rest. That's because they train them for that and that's how they promote themselves, but in independent developer tests, it fell to 66th place,” the Doctor of Communications contrasts.

The researchers who propose the term "Potemkin understanding" emphasize that large language models can explain concepts but not apply them. They are able, for example, to define very well that a haiku "is a type of traditional Japanese poem consisting of three lines with a 5-7-5 syllable pattern," according to the automated Meta chat included in the WhatsApp application. When attempting to create one, however, they fail:

Cherry blossoms

They dance in the soft wind

“Spring is coming.”

When you ask ChatGPT to correct the poem, it detects the errors, but offers an edit with new errors that Meta detects, but is unable, once again, to correct. And so on, in a loop.

“When they have to go out into the real world, they're pretty screwed ,” Babio simplifies, while simultaneously issuing a warning. “You have to see how much more screwed they are than the average human being.”

More noise than nuts

Experts agree that advertising inflates expectations beyond real capabilities, obscuring limitations. "I think there's a mix of optimistic promotion and exploitation of our automation bias for a marketing campaign," analyzes María Vanina Martínez, a PhD in Computer Science and senior scientist at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC). For her, this type of manipulation is an indirect way of exerting pressure on the labor market.

“It's a campaign that promotes the replacement of human beings to increase efficiency and production, as if that were our ultimate goal. Clearly, from a resource and power efficiency perspective, automation and the dehumanization of processes seem to be the only path.” Babio painfully confirms this: “These people want to question human labor, to question the idea that everything is replaceable.”

What seems clear is that these developments are not what they promise. “They are powerful, yes. They can reproduce and imitate how humans write, but that doesn't necessarily lead us to think they can reason like us. Perhaps for some very specific things, imitation is very good because they've seen many examples, but the great language models don't reason. At least not under the definition of reasoning that humans use,” Martínez argues. Babio wonders if that's enough to rule out understanding. “It could be another system of drawing inferences, another type of understanding,” he suggests.

Better together

The three experts agree that the best way to address these shortcomings is through technological convergence. "Some of these limitations can be improved if we complement the generative AI we have today, based purely on data-driven machine learning, with techniques and models that allow us to represent knowledge."

A development that goes beyond the enormous amount of information humans leave on the Internet and is capable of offering both specific and general solutions. Something like a fully self-contained Artificial Intelligence.

Auto-cannibals

These models are also heading toward a more complex destiny than the illusion of thought: autophagy. If everything they can offer is taken from the internet and the network is filled with self-generated results, they will end up basing their work on their own responses. “Now we have a problem with the percentage of data generated by the systems, which, in the end, feed off their own outputs, regurgitating averages,” warns Martínez. To top it all off, these averages are biased. “The internet is not diverse; most of the content comes from male, white users from the United States and Europe.” A familiar formula for sustaining established inequality.

"We have to be able to use technology critically and understand that no narrative surrounding it is neutral. There are vested interests. Because, as they always say, if something is free, you're the product," warns the Argentine scientist who researches at the CSIC.

“This depends partly on us, but also on our governments. They must give us the tools to learn how to use them and protect us with appropriate regulation. While technology is neither good nor bad and depends on how it is used, that cannot remove the responsibility from those who subject us to its use as if it were all inevitable and the only way out is to accept it as it is or lose the benefits.”

ChatGPT has provided a good introduction to this article and provided a good example of "Potemkin comprehension." In explaining it, however, something strange emerged: "That's what humans do naturally, and what language models still only simulate under certain conditions." Perhaps she's just being silly.

El Pais, Spain Maria Victoria Ennis , Buenos Aires - August 28, 2025